Discoveries beyond doubt

How bones, bronze and a Han historian rewrote our memory of the Shang era, a key period in the early development of Chinese civilization, Wang Ru reports.

Sima Qian is celebrated as the top authority on the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC). The problem is, he's virtually the only authority on the Shang Dynasty.

The Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) historian described the Shang Dynasty and the lineage of Shang kings in Shiji, or Records of the Grand Historian, the foundational text of Chinese history dating back to the first century BC. But doubts surrounding his writings long persisted due to the scarcity of other historical records left by the Shang.

The groundbreaking discoveries of inscribed oracle bones from the Yinxu Ruins, a late Shang capital in Anyang, Henan province, in the late 19th century finally dispelled these doubts by providing tangible evidence of the Shang's existence.

Moreover, since Shang people worshiped their ancestors and recorded the related fortune-telling on the bones, they left a lot of information about Shang kings. By collecting tidbits from the bones, scholars have pieced together a complete lineage of 31 Shang kings.

By comparing the chronology garnered from the bone inscriptions to Sima's texts, experts found his writings are mostly reliable, with only minor disparities between the two kinds of records.

"It's quite accidental. If not for Shang people's ancestor worship, we would have been unable to extract the lineage from oracle bones or validate the continuity of the Shang Dynasty," says Gao Hongqing, a researcher at the Capital Museum in Beijing.

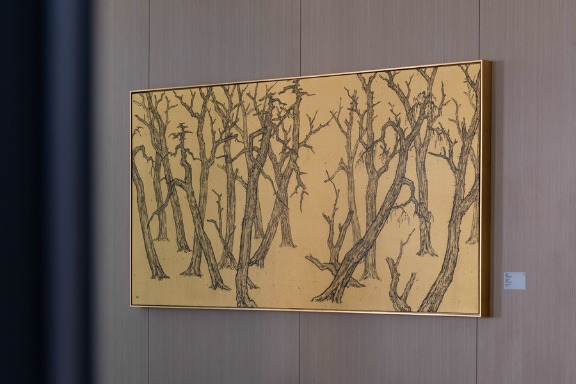

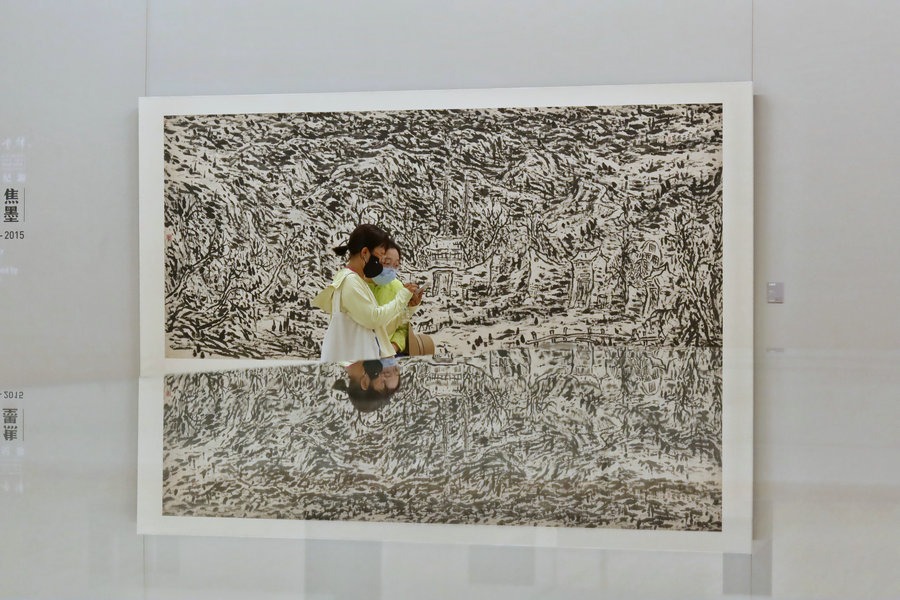

The fascinating story of inscribed oracle bones is portrayed at the ongoing exhibition, This Is the Shang, at the Grand Canal Museum of Beijing affiliated with the Capital Museum.

As a highlighted exhibition celebrating International Museum Day on May 18, the show has attracted many visitors, who've continued lining up every day since its debut on May 19. It will run until October.

Capital Museum deputy director Tan Xiaoling says the exhibition offers a panoramic view of the Shang and its role in the origins and early development of Chinese civilization. It displays 338 cultural relics from 28 archaeology institutes and museums nationwide.

Archaeologists have long considered the Xia (c. 21st century-16th century BC), Shang and Zhou (c. 11th century-256 BC) dynasties as key periods to study China's early formation.

"Together with the Xia and Zhou dynasties, the Shang Dynasty has exerted a profound influence on the fundamental trajectory of Chinese society for thousands of years," says Tan.

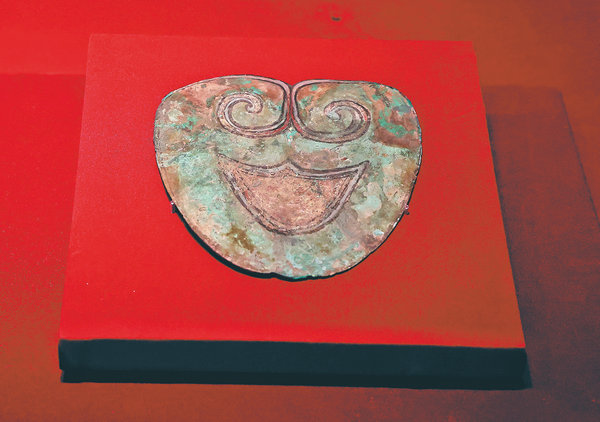

Displayed relics include inscribed oracle bones — the most iconic artifacts from this era — alongside bronze, pottery and jade items.

Oracle bones were used for fortune-telling, as well as recording and composing China's earliest-known formal writing system, jiaguwen. In 2017, the inscriptions were listed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register program.

Gao, who is also curator of the display, says it shows the two versions of Shang kings' lineage from Shiji and the inscribed bones, allowing visitors to make their own comparisons. It also shows a bone fragment that provides insight into the names of certain Shang kings.

Intricate artifacts

The Shang Dynasty is renowned for its bronze artifacts. Some of the most precious treasures borrowed from museums nationwide are on show at This Is the Shang.

For example, the reunion of two owl-shaped wine vessels found in the tomb of Fu Hao, China's first known female general and consort of Shang king Wu Ding, has attracted much attention.

They were unearthed together in 1976 but separated soon after for exhibition. One now belongs to the National Museum of China in Beijing, while its sibling belongs to the Henan Museum in Zhengzhou, Henan province. They differ by less than 1 centimeter in length and 0.7 kilograms in weight, and otherwise exhibit nearly identical formats, patterns and inscriptions. Their reunion after decades marks a historic occasion, says Tan.

The exhibition sheds light on the intricate craftsmanship behind the creation of Shang bronze ware, showing how these artifacts are not only metal objects but also reflections of social relations.

"Making bronze items was quite intricate and required involvement of many people from different parts of the country. It included mining copper ore, smelting it, crafting a clay model adorned with intricate patterns, creating an outer mold and pouring molten copper into the space between the mold and model," Gao explains.

"When the liquid metal solidified, the outer mold was broken to reveal the cast bronze vessel with intricate designs. Compared to making jade and bone artifacts, this was extremely time-consuming and labor-intensive. For example, a Shang ding cauldron with exquisite patterns from Yinxu, now stored at the National Museum of China, weighs over 800 kilograms. Just imagine the work required to produce such a remarkable piece!

"Therefore, making them required a handicraft-production system to organize the labor force, and that cannot be achieved without political power. Crafted as burial items for the aristocracy, these artifacts were the embodiment of power during the Shang era."

The Shang also sired a bronze cultural circle that extended its influence eastward to present-day East China's Shandong province, westward to Northwest China's Shaanxi province, northward to the Great Wall and southward beyond the Yangtze River. The exhibition details this spread by showing many Shang-style bronze artifacts from other places.

For example, the bronze zun and lei drinking vessels unearthed from the Sanxingdui site in Guanghan, Sichuan province, dating from 4,500 to 2,900 years ago, are on display. They're very similar to their counterparts found from China's Central Plains, demonstrating cultural exchanges at that time.

"We show many similar artifacts from different places or comparable patterns on various vessels, inspiring visitors to consider the influence of Shang bronze culture," says Gao.

"The bronze cultural circle laid a foundation for the vast territory of the Zhou Dynasty, following the Shang, and the formation of a great unified dynasty during the Qin era (221-206 BC)."

Shining legacy

Spanning over 500 years, the Shang Dynasty deeply influenced the following dynasties and even China today, as the exhibition shows.

The Shang laid a foundation for rituals and music systems, which were influential frameworks crucial to upholding social order. While conventionally credited with originating in the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC), their roots can be traced back to the Shang era.

For example, an important Zhou Dynasty custom is to distinguish social status through the use of ding cauldrons and gui — bronze vessels for cooking and serving food, respectively. For example, Zhou kings could use nine ding and eight gui, while feudal lords could use seven ding and six gui. Lower-status nobles had fewer, and ordinary people could not use them at all.

This convention evolved from an earlier version in the Shang Dynasty, when bronze gu and jue wine vessels often appeared as sets in tombs. The number clearly conveys the social status of the tomb's occupant.

"By exhibiting these ritualistic artifacts and musical instruments, we want to show the Zhou's ritual tradition was a continuation of Shang practices, with numerous Zhou musical instruments evolving from their Shang predecessors," says Gao.

The exhibition also features an area showing artifacts that were prototypes for characters and their weapons in China's top-grossing film, the animated blockbuster Ne Zha 2.

For example, the images of two guardians in the film are inspired by a bronze head with a gold mask unearthed from the Sanxingdui site. And their weapons are believed to draw inspiration from a bronze yue (ceremonial axe) with tiger patterns and a notched bronze sickle-shaped implement from Gansu and Shaanxi provinces shown at the exhibition.

"The film's director skillfully incorporates elements from Shang Dynasty relics into his film. This demonstrates a good way to bring new life to old artifacts and history closer to modern people," says Gao.

Contact the writer at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn